As we step back in time to India’s post-independence era, the 1950s were marked by significant changes. Our newly liberated nation adopted a Westminster-style parliamentary system of government at both the federal and state levels. However, the scars left by British colonial rule—ethics, wealth depletion, and reduced productivity—still lingered. With a population of 50.82 million citizens, India faced a critical challenge: how to feed its people with limited food grain production.

At that time, India heavily relied on importing food grains, particularly wheat, from the United States. The national reserves were depleting rapidly, and self-reliance and self-sufficiency seemed like distant goals. It was against this backdrop that a revolution in agriculture became imperative.

The Visionary Scientist: Mr. M.S. Swaminathan

Enter Mr. M.S. Swaminathan, an agricultural scientist who would play a pivotal role in reshaping India’s destiny. In 1953, during a meeting at the American Institute of Biological Sciences, he learned about newly developed genetically modified hybrid varieties of wheat. These varieties were remarkable—they responded well to external fertilizers and irrigation, resisted water lodging, and promised yields 2.5 times greater than native varieties.

From Trials to Nationwide Adoption: The Green Revolution Unfolds

Swaminathan’s journey began with small-scale trials across 114 districts. These trials introduced the High-Yielding Varieties (HYVs) of wheat and paddy. As their success became evident, the revolution expanded, covering the entire country. By 1965-66, the cultivable area for HYVs had grown from 1.89 million hectares to a staggering 72 million hectares by 2023-24 achieving a total food grain production capacity of 72 million tons in 1965-66 to 329 million tons in 2022-23 becoming one of the World’s top 3 exporters in food grains.

It’s Impact:

Before the Green Revolution, native farmers relied on indigenous seeds and followed diverse cropping systems—rice, millets, sorghum, maize, and barley. Rice and millets dominated their fields. However, the introduction of HYVs transformed the landscape. Rice and wheat took center stage, impacting the overall diet of the nation. The era from 1967 to 1968 witnessed an extensive and intensive transformation of agriculture, aptly termed the “Green Revolution.”

1.Dependency on a Limited Set of Food Grains:

- The Green Revolution significantly boosted the production of staple food grains, particularly rice, wheat, and maize.

- While this led to increased availability of these grains, it also resulted in a heavy reliance on just a few crops.

- Health Implications: Consuming predominantly rice and wheat can lead to health-related issues, as a diverse diet is essential for optimal nutrition.

- Our culinary habits have also centered around these grains, limiting the variety of foods we consume.

2.Farmers’ Dependency on External Inputs:

- Although India achieved self-sufficiency in food grain production, farmers now rely heavily on external inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides, and hybrid seeds.

- Cost of Production: The increased use of these inputs has raised the cost of production for farmers.

- Profit Realization: Despite higher yields, many farmers struggle to realize sufficient profits due to rising expenses.

- In the past, farmers practiced integrated farming with diverse crops, which provided multiple income sources. The shift to monocropping has increased the risk of financial losses.

3.Depleting Water Tables:

- The Green Revolution introduced water-intensive crops, leading to the expansion of advanced irrigation systems.

- Unfortunately, little attention was given to recharging groundwater.

- In regions like Haryana and Punjab, where the Green Revolution was implemented extensively, water availability is now a major challenge which has led to declining productivity over the past few years.

- World Bank Data: Approximately 63% of India’s districts face falling groundwater levels.

- Poverty Impact: Poverty rates are higher in districts where groundwater tables have fallen below 8 meters, affecting small farmers disproportionately.

The adverse effects of overexploitation, particularly in regions where intensive farming practices prevail. The need of the hour is a shift towards sustainable approaches that prioritize conservation while maintaining agricultural productivity.

- Native crop varieties are less water-intensive and can significantly alleviate pressure on ground water resources.

- By diversifying crop selection, farmers can achieve a more balanced water usage pattern, promoting long-term sustainability.

- Implementing strategies such as rainwater harvesting and artificial groundwater recharge can help restore aquifer levels, ensuring a reliable water supply for future generations.

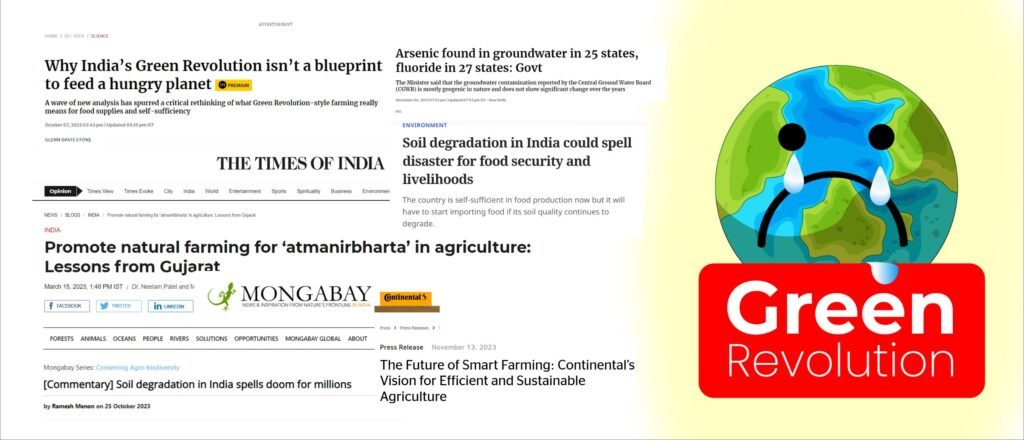

4.Groundwater Pollution:

- The intensive use of chemicals in agriculture—such as nitrates, sulfates, and heavy metals—poses a significant risk to groundwater quality.

- When these chemicals are sprayed onto crops or soil, a substantial portion mixes with water and leaches down into the groundwater table.

- Human Health Hazards: Contaminants like arsenic, nickel, copper, chromium, lead, mercury, and cadmium are associated with health issues, including cancer.

- Given that 85% of India’s domestic water consumption relies on groundwater, this pollution directly affects human well-being.

5.Excessive Agro-Chemical Usage:

- Every year about 62 thousand metric tons of Agro-chemicals are going to our Indian Soils just to control Pests and diseases.

- But the harsh reality is that farmers often apply 70% to 80% more chemicals to their crops than necessary.

- This excessive application of chemicals results in biomagnification, a process in which these substances progressively accumulate in the environment and organisms, posing serious health risks to ecosystems and human populations.

- The belief that “more chemicals mean more yield” has become a common refrain among farmers. However, it’s essential to strike a balance between productivity and environmental safety.

- There is a global shift towards prioritizing chemical-free farming practices to align with the Sustainable Development Goals set to be accomplished by 2030. This emphasizes a move towards sustainable agricultural methods that minimize or eliminate the use of chemicals, promoting environmental health and long-term viability in farming systems worldwide.

6.Deterioration of Soil Fertility:

- Soil health is intricately linked to the presence of microorganisms—the unsung heroes of agriculture.

- Unfortunately, excessive chemical use has harmed these beneficial microbes, affecting nutrient availability, soil structure, and plant growth.

- The overapplication of external fertilizers, including NPK (nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) and micronutrients, disrupts the nutrient cycle.

- Carbon Content Decline: Indian soil now contains less than 0.75% carbon in cropped areas. Carbon is crucial for plant growth—it’s the skeleton nutrient.

- This reduction in soil carbon content raises alarms for future food security.

The Green Revolution had far-reaching effects, and it’s essential to consider its implications. Here are some individual steps we can take to create a positive impact for the future:

Remember, individual actions collectively create a significant impact. By making conscious choices, we contribute to a healthier planet and a better future for all.

19 Feb 2024

19 Feb 2024  6 Min

6 Min